- As people travel, they carry plants and animals with them (on purpose or accidentally) that are introduced to other habitats and ecosystems with no natural barriers to their activities or population growth.

- Anti-fouling paints and high speed prevent organisms from attaching to modern steel-hulled boats.

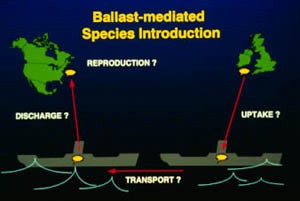

- Ballast water does serve as a home for many marine organisms

- It is estimated that at any one time there are over 3000 species of marine organisms moving around the oceans in the ballast water of ships.

- Some invaders are not noticed for years or perhaps decades in the new environment, whereas others can affect new areas immediately.

- Biological oceanographers and marine biologists now fear an ecological revolution: „biological homogenization“ by removal of natural barriers

- James Carlton (Science, 1993): „No introduced marine organism, once established, has ever been successfully removed or contained, or the spread successfully slowed.“

- Chesapeake Bay lists 160 alien species and 40 species of unknown origin

- San Francisco Bay: more than 100 nonindigenous species established in the last 100 years; one new species every 24 weeks since 1970

- Ballastwater of Japanese commercial ships calling Oregon contained 1500 copepods >200 other zooplankton and juvenile fish per m³; 367 types of organisms were introduced within a 4-hours study period

- Dumping of ballastwater in US harbors: ca. 40,000 gallon per minute (NOAA)

- Estimated total cost of invasive species: $123 billion per year (as of 1999)

- Ports of Baltimore and Norfolk alone receive 2,834,000, and 9,325,000 metric tons of ballast water, respectively, each year, originating from nearly fifty different foreign ports

- More than 90% of vessels arriving at Chesapeake Bay ports carried live organisms in ballast water, including, but not limited to, barnacles, clams, mussels, copepods, diatoms, and juvenile fish.

- Nonindigenous Aquatic Nuisance Prevention and Control Act: voluntary regulations for ballast water exchange for Great Lakes bound ships since 1990; law since 1993. No other ballastwater management law worldwide yet!

The ‘aim’ of exotic species is not to take over an estuary or clog a factory’s water pipes, but rather to simply survive and reproduce.

- They are hardy, surviving a trip inside a ship for thousands of miles.

- They are aggressive, with the capacity to outcompete native species.

- They are prolific breeders, and can take quick advantage of any new opportunity, and

- They disperse rapidly.

Invasive species can inflict damage on ecosystems by:

- outcompeting native species,

- introducing parasites and/or diseases,

- preying on native species, and/or

- dramatically altering habitat, e.g., rearranging the spatial structure of an ecosystem

Examples of Nonindigenous Species

-

-

-

-

-

-

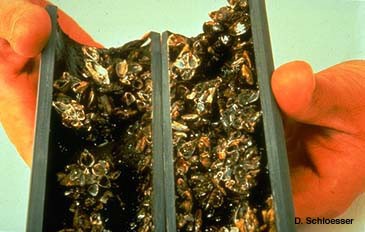

- Name: Dreissena polymorpha

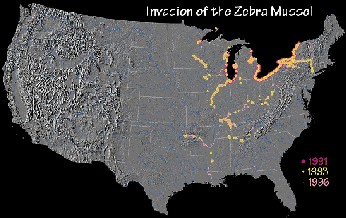

- Origin: Caspian Sea, via canals into the Baltic Sea, by ship to the Great Lakes

- Introduced: ca. 1986

- Life cycle: rapid growth, sustain cold winters, extreme number of eggs, active filter feeders (change plankton bio- mass and composition), settle on both hard and soft bottom

- Effects: decreased fish stocks, higher water clarity so that bottoms are recolonized by rooted plants, immense clogging of pipes, water inlets, power plant pipes, fouling of boat hulls and even engines

- Economic costs: ca. $3 billion so far

- Mitigation: none available, attempts to dam further spreading by public education of boaters

- Giant Jellyfish in the Gulf of Mexico

-

June

2000: first „Australian spotted jellyfish“ Phyllorhiza punctata

occur off Mobile Bay

- Last week of June 2000: first reports of jellyfish catches by shrimpfishers

-

Early

July 2000: jellyfish, normally 5-15 cm in diameter, reach upto 50 cm in

size (average 35 cm)

- August 2000: peak of jellyfish abundance, mostly west of the Mississippi River mouth; jellyfish are accumulated in bands 1000 m long and 100 m across, drifting westwards with the predominant current off the LA coast. Numbers reach 50 animals per 100 m²

- October 2000: yet another giant jellyfish (Cyanea sp.) of unknown origin and >70 cm in size covers the coast from Florida to the Mississippi

The green shore crab (Carcinus maenas), origin: Europe; spreads from San Francisco Bay northwards since 1990; reduces commercial dangeon crabs; economic damage $44 million

The parasitic barnacle Loxothylacus panopaei from the Gulf of Mexico and South Florida infects various crabs in the Chesapeake Bay

Water flees (Cladocera) from the Caspian Sea spread into the Baltic and the Great Lakes

Mass develop-ment of starfish threaten corals in Austalia

The cordgrass Spartina was used to protect coastlines from erosion. It invades mud flats rich in invertebrates and birds, changes the coastline, replaces diverse communities, produces monotypic stands, promotes agricultural reclamation and loss of salt marsh habitats

The Masterpiece: Zebra Mussels in the Great Lakes

The story of Caulerpa taxifolia

-

Early

1980‘s: the curator of the tropical aquarium at Stuttgart, Germany, noticed

the exceptional properties of a tropical green alga for display in aquaria:

fast growth, tolerance to low temperatures, rigid survival

-

The accident:

between 1984 and 1985, some specimens got into the Mediterranean by washing

tanks at the honored Musée Océanographique de Monaco

- Mass development: only 6 years later, Caulerpa occupied the French coast 5 km off the Musée and overgrew everything from the surface down to the bottom of the euphotic zone, on hard botton as on mud and sand

- Status: By now, it covers almost the whole coast from Spain, France, Italy to Croatia.

- Toxins prevent grazing by herbivors, sometimes toxic to fish

-

Biological

control: the tropical sea slug Elysia was set free in the Mediterranean

to control Caulerpa; the effect: the green alga continues to grow, but

other seaweed are even further reduced by the sea slug‘s appetite. Now

also off California!

- By-catch: non-commercial animals with no use, dumped back into the sea; most severe in shrimp fisheries: 4.2 kg fish for each kg of shrimp (GoM); can cause changes in benthic communities and oxygen problems (degradation)

- National Ballast Water Information Clearinghouse

- Summaries of 20 articles published by researchers on nonindigenous species introduction

- Ballast Water and Exotic Species Web Sites

- Biodiversity and Conservation: A Hypertext Book by Peter J. Bryant

- Online book „Nonindigenous Aquatic and Selected Terrestrial Species of Florida by the University of Florida

- The History and Effects of Exotic Species in San Francisco Bay

- A field guide to aquatic exotic plants and animals in the Great Lakes

- USGS Florida Caribbean Science Center on nonindigenous species